In 1922 my great grandfather and his father built a cottage. Located on the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, on the shore of the Straits of Mackinac (which connects Lakes Michigan and Huron), its ostensible purpose was to provide a refuge from seasonal allergies. Whether it succeeded in doing so 100 years ago I’ll never know, but today it certainly doesn’t. I’ve been visiting regularly (or semi-regularly) for almost two decades and not once have my allergy symptoms abated while there. Nonetheless, it is still a beautiful place filled with history and meaning and a welcome refuge from allergies more social and technological.

My grandparents were the unofficial caretakers for decades, always the first ones to open up the cottage in the spring and close it again in the late summer. Most of my trips were with them, tagging along to help with the labor required to maintain a very old and surprisingly makeshift structure. The itinerary fluctuates with each visit, and mostly the point is to move and do as little as possible, but one constant is a day trip to Mackinac Island.

Depending on who you ask, the name Mackinac derives from a French transliteration and subsequent English shortening of an Ojibwe and/or Odawa word (Mishimikinaak or Michilimackinac) that means, “great turtle.” Although Turtle Island is used by many indigenous peoples to refer more broadly to the entirety of the continent, it would seem that, for the Anishinaabe, Mackinac Island was the place where human life began on earth. I am ashamed to admit it has taken this long for me to learn this. Perhaps had I known sooner I would have approached each visit differently, with more reverence. Though it is just as likely that the knowledge itself wouldn’t have changed much, because the way I relate to that place matters more than the knowledge I have about it.

And it was just this, how we relate to a place and its inhabitants, especially a place that we only visit briefly, that’s been on my mind since returning from my latest trip to the cottage and island.

As I walked around Mackinac Island I found myself thinking about Thoreau’s only trip out West, but I wasn’t sure why.

The story goes that Thoreau caught tuberculosis sometime in 1835, but didn’t really get ill until the winter of 1860, eventually dying from it in the spring of 1862. He believed that he caught a cold while counting tree rings in bad weather on December 3, 1860, but I recently discovered another theory, that he actually caught this final cold from Bronson Alcott, who caught his illness from a teacher’s convention. Sounds eerily familiar that, contracting a respiratory illness from a large gathering of people.

Regardless, the advice Thoreau received—common at the time—was to travel someplace warm and humid to help alleviate his symptoms.

The threefold recommendation for relieving lung congestion was to get outdoor exercise, to maintain a bland diet, and to breathe air in a more conducive environment. Thoreau’s everyday lifestyle already met the first two criteria.

Corinne Smith, “The Journey West to Minnestoa” in Henry David Thoreau in Context

In May of 1861 Thoreau ultimately settled on Minnesota rather than the West Indies as suggested by his doctor. There were a few reasons for this: first, he had personal connections and relatives in Minnesota with whom he could stay; second, traveling through the South was not a good idea given the Civil War; and lastly, “New Englanders who had visited or settled there had reported to Boston newspapers that their breathing had improved.” (Smith, “Journey West”)

What I must have known (but forgotten) was that he visited Mackinac Island on his return journey. Walking around the island must have stirred my unconscious memory of this fact and forced its way into my awareness.

The men spent four days here [on Mackinac Island], and Thoreau filled four pages of his field notebook with a “Plants of Mackinaw” inventory. Topping the list were the arborvitae trees that seem to grow everywhere, “esp. on rocky steeps about sides of I[sland].” He also saw apple trees and lilacs still in bloom here in late June, when back home they would have bloomed in May. The men climbed to the top of Arch Rock, one of the island’s higher natural overlooks. Here, above the forty-fifth parallel and surrounded by water, the air could get chilly, even in summer. Thoreau noted that he “Sat by fire July 2nd.”

Corinne Smith, “The Journey West to Minnestoa”

It’s interesting that Thoreau’s journey through the Michilimackinac region, including Mackinac Island, was part of an attempt to heal and recover from illness. While certainly more urgent than escaping seasonal allergies, that both my family and Thoreau sought restoration in that place connects us in a way I never expected.

Even though I have been coming to this place for years my relationship with it has been mediated primarily through my family’s habits, especially my grandparents. I went the places they went, heard the stories they knew, and was attentive to the things they were attentive to—I had no one else to instruct me or guide my attention elsewhere. Since the main reason for visiting the cottage and island was to escape the allergies of everyday life, seeking out scenery that made that easier was the means to that end. In other words, finding a view of the world that was conducive to escape meant ignoring or hiding from view anything that threatened to pull your attention back to those things you were trying to avoid.

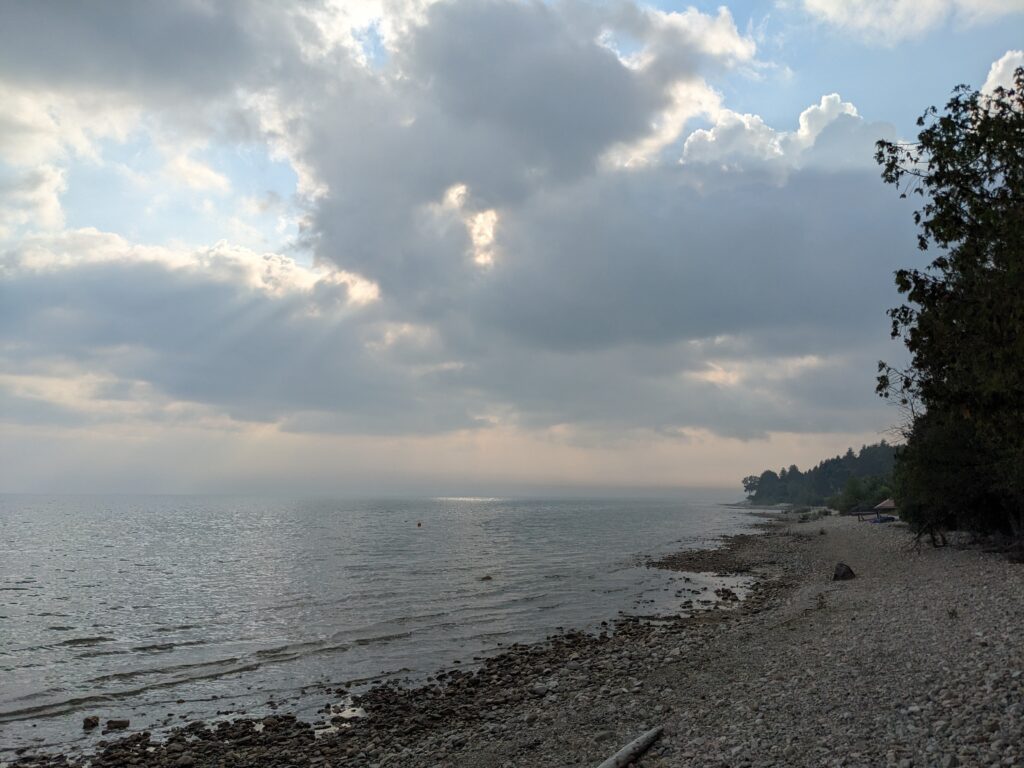

So it seemed natural to me to focus my attention on finding the least obstructed views of the vast expanse of sky and water, both from the lake shore and the highest points of Mackinac Island. In truth they were hard to escape: the dramatic sunsets and empty horizon made looking elsewhere difficult. And what better way to escape than by minimizing what enters your perception—water and sky so completely filled my view that nothing else could enter in.

All distant landscapes seen from hill tops are veritable pictures which will be found to have no actual existence to him who travels to them.

Thoreau, Journal, 1 May 1851

The views were inspiring, both from the cottage and from the island, but they were as empty as they were full. In other words, the views those places afforded—a view of everything—managed to obscure the specificity of those places. It was a view of both everything and nothing simultaneously.

My relationship to those places, like all relationships, was shaped as much by what I wasn’t seeing as by what I was. Or, to put it more bluntly, my experience of that place was a direct result of what I ignored: the chunks of flint hidden in the endless rocks that lined the lake shore, the square holes left by pileated woodpeckers in the arborvitae, the red squirrels running back and forth across the front of the cottage, the American redstart singing every morning from the swamp behind the cottage, the lilacs still in bloom even after the ones back home had already faded—all of these had escaped my attention in years past.

Many an object is not seen, though it falls within the range of our visual ray, because it does not come within the range of our intellectual ray, i.e. we are not looking for it. So, in the largest sense, we find only the world we look for.

Thoreau, Journal, 2 July 1857

On this trip’s visit to Mackinac Island I had a close encounter with an American redstart (setophaga ruticilla). At the foot of a steep and rocky slope (that lead to Arch Rock) I could see a small bird moving from branch to branch in the undergrowth. As I approached it stopped moving long enough to permit me a good view of the brilliant red and orange patches on its chest and tail, but it wasn’t until it started singing that I realized I had heard the same melody earlier in the day at the cottage. Through this encounter the familiar became novel—the world expanded at our meeting.

I have never visited Walden Pond or walked through the streets of Concord, but I have climbed to see Arch Rock, wandered seemingly back in time to see the lilacs still in bloom, and sat under the arborvitae near water’s edge. Here on Great Turtle Island, the beginning of the world, is the only place I know that Thoreau and I have both been. We have seen the same views, felt the same cold summer air around a fire, and maybe even walked the same trails. Strange that it took learning (or re-learning) about our shared experience of this place for me to begin to appreciate—to see—the other inhabitants of Michilimackinac, those who have been here all along but unseen by me.

Among other things, Thoreau continually offers me new ways to be attentive to the world I inhabit daily, my home. But I’m now beginning to realize that he has also given me a way to appreciate the “infinite extent of our relations” in all places, even those I only visit briefly. And those relations are not just geographically or spatially infinite, but temporally infinite as well. Walking on Mackinac Island or on the shores of Lake Michigan, his life and mine are no longer separated by the distance of years but we meet in that place in a more perfect time.

Of what manner of stuff is the web of time wove—when these consecutive sounds called a strain of music can be wafted down through the centuries from Homer to me—And Homer have been conversant with that same unfathomable mystery and charm, which so newly tingles my ears.

Thoreau, Journal, 8 January 1842

That both Thoreau and I have heard that same warbling melody, in the same place no less, seems likely to me. And just as the strain of music from a music box connects Thoreau to Homer, so too does the charming and mysterious song of the redstart connect Thoreau to me: we meet in the present moment when my past and his future collide in that place. “This coincidence of past and future in a present is what Thoreau calls ‘perfect time.’” (Branka Arsić, Bird Relics)

My relationship to the places I inhabit, however briefly, is shaped by what I look for—what I see and hear as well as what I ignore. Those plants and animals, those rocks and that water are infinitely related to me in that place.

I don’t mean to suggest that, like the panoramic views I sought where the view of everything was a view of nothing, I am infinitely related to all things in all places at all times. Rather, I mean to suggest that the particular and specific flora, fauna, geology, and hydrology of a particular and specific place relates to me as an inhabitant of that place when I look for and see that world and those relations. Otherwise the idea of being infinitely related becomes something that infinitely separates. It is through the specific and particular that the infinite is entered, the one center from which infinite radii are drawn.

Though Thoreau and I are separated by time, in that place we are connected and related—we are relatives. I have never found relief from my seasonal allergies nor did Thoreau find any healing from his much more serious illness, but we have both sat under the tree of life and found that the infinite extent of our relations begins there, in that place.

I realized during this trip, while walking in his steps, that I had not yet seen that world and those inhabitants. If I am a relative I am not yet a good one; it will take many more trips before I can properly appreciate and relate to those citizens of Michilimackinac. For now, at least, I am learning to see their world and find my place in it.

One response

Thanks Nathan. I really like that. I was exposed to gestalt psychology early on. And it has had a similar effect on my life. The Esalin institute used to have good books on exercises based on gestalt psychology. How about learning to experience the things that you don’t normally.